Baby O and The Universe

Sep 09, 2023

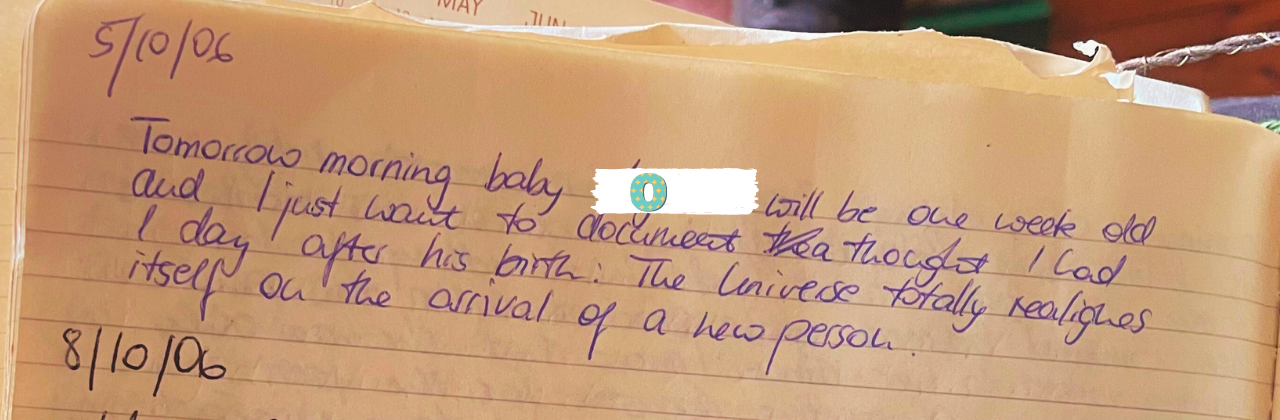

On October 5h, 2006 I wrote in my diary:

‘Tomorrow morning baby O. will be one week old and I just want to document a thought I had the day after his birth: The Universe totally realigns itself on the arrival of a new person.’

Time of birth: 07:44.

This was the first time I witnessed a baby land into the arms of friends. When I got to watch them become a family, they had been friends of ours for many years. It struck me that although I had struggled to see them as anything other than a couple all the way through their pregnancy, the very moment they became parents, I couldn’t imagine them any other way anymore. It was as if their baby had always been there, right on his mother’s chest, and for a moment I thought that I understood infinity and the wheel of time. Of course by that stage I hadn’t slept for 30-something hours and we were all high on oxytocin, an experience much reminiscent of a 1990s dance party but nevertheless, I felt it was worth documenting that thought. This is the privilege of observing birth in its unfolding, you get glimpses at the fabric of life in a way very few people do. Those glimpses can come at four in the morning during a caesarean section in a brightly lit theatre or next to a birth pool and I think they are more than just the thoughts generated by a mind deprived of sleep.

They are universal TRUTH.

The previous four pages in my diary are dedicated entirely to outlining little baby O.’s birth story as I had witnessed it. The way we met at the admission’s unit and the midwife said ‘You are only 2cm and you are acting like someone who is about 9’ (I was generous in my elaborations about what I thought of *that* midwife). Instead of taking the midwife’s offer of being ‘admitted for pain relief’ we went home, lit some candles, ordered pizza, ran a bath and listened to some music. We laughed and sang and told stories. To this day I cherish these memories. When we got back a few hours later baby O’s mama had almost established in labour and we went to the antenatal ward for a while. She was in the bathtub with her husband and me by her side.

I mention in my diary that I felt nervous coming up to this labour because we would be at my teaching hospital, I didn’t want to be in a tricky situation as an advocate who was also a student midwife there.

The retelling of this birth just a year into my midwifery training reveals in equal parts my naivety and my curiosity, but also an astuteness and honesty that is disarming looking back at it now. I was aware that, where I worked, respecting and facilitating birth physiology ranked second to the medical model of birth and I had also spotted that people who support women unconditionally could be seen as troublemakers by those who align with the institution. The physiology camp was badly outnumbered even then and it is even more so now. My diary is also full of elaborations of how I understood that this was the way it was set up and I tried my best to stay away from judging people for their convictions and see them for the people they were (sometimes more successfully so than others). I recognised that every single practitioner, whether I agreed with their overarching understanding of the landscape of birth work or not, started out on their path because they felt passionately about helping families in pregnancy and birth and I respected them for that. It's when that passion is gone and the compassion has left with it that I just cannot find any way of justifying some of the behaviours that occur within maternity care. To me 'compassion fatigue' is a lazy way of trying to justify what I see as a systemic problem within the medical complex.

The night of baby O’s birth we encountered many of my future colleagues. I wrote ‘When we arrived in the hospital a lovely midwife called T. who I got to work with in the delivery suite looked after us. On examination [my friend’s cervix] was 3-4 cm dilated. We were admitted to the antenatal ward where midwife S. looked after us. She was lovely and I do hope that I will meet her again during my next placement. [...she told my friend] to focus on the fact that this labour was going to end and that she was going to hold her baby very soon. It helped [my friend] a lot when S. held her gaze.’

Eventually we went to the labour ward and I commented that ‘my heart sank’ when I saw who the sister in charge was. This is something that every student midwife, every junior midwife and every experienced midwife will recognise and ever since writing this blog I have had a number of personal messages from midwives who speak about being worried about going into work simply because of who they might be working with. Some of it is down to the fact that as a shift worker you have to work with so many different people and you just love some people more than others and some of it has to do with how you might be spoken to by the person in charge or your colleagues. In hindsight I can honestly say that I have personally experienced mostly positive relationships with my seniors and my peers over the years but that night I was scared of how this birth might go with that sister in charge if there were big decisions to make.

Thankfully my friend's labour ward midwife was beyond great and we saw very little of the sister in charge. The midwife slipped in and out to do observations in such a quiet manner that it seemed that she wasn’t even there. I made a mental note that this would be me once qualified. The little man was born with his mother on her all fours on a mat on the floor. I was kneeling next to my friend and I remember kneeling in amniotic fluid and blood when he gushed out. I cycled home, my jeans stuck to my knee feeling as though I had finally had a true initiation into the rawness of birth.

Washing my body before falling into bed felt like a baptism of sorts.

It was in many ways my baptism into the dogma of regulated midwifery. The midwifery model of care, I learned, was distinctly different to the medical model of care. I was fully committed to this belief and like many of my colleagues I had a total blind spot for the fact that they are one and the same. I saw ‘promoting normality’ as a midwife’s job and, to me, the fact that my friend had given birth to her son on the floor on all fours was radical to me!

Gravity, gravity, gravity. That's where it was at!

While moving intuitively and freely is a desirable feature of a physiological birth, I overlooked some fundamental pieces to the puzzle. Prescribed positions even if that is ‘kneeling over the back of the bed’, one that was to become a favourite of mine, are ultimately foregoing intuitive movement. That’s neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’. It is, however, an observation worth making. Any suggestion from the outside engages a woman's forebrain, her thinking mind. We take her out of her limbic brain where instinct and intuition are accessed and this disrupts labour. This is not the fault of individual care providers. Many women want to be told what to do. Am I pushing right? Is this a good position for birth? I don't know what to do. Midwives hear this a lot. In fact this is the most common dynamic between women and their midwives or even their doulas. It's the hierarchy we have created. The expert and the lay person. Women outsource responsibility and give up their autonomy and trade it for the expertise of midwives and doctors. Most of us don't know how to to tap into our instincts anymore and we don't trust our bodies. Could pregnancy be a time to learn how to find answers in yourself rather than getting educated about your ‘informed choices’ and about how to ‘promote normality’ in birth?

My R.O.A.D. To Birth Coaching Program is designed to help you with this and it is available as part of my one-to-one packages. Email me at [email protected] if you would like to work with me.

None of these questions had come up for me yet and I came away from the experience of watching my friends become parents totally elated and with a desire to get ‘good’ at being a midwife. Getting vaginal examinations ‘right’ for example was very high on my list of things to learn and I know this is the case for many student midwives. I took for granted that the way we ‘managed labour’ was something I had to learn if I wanted to be good at my job. You ‘listen in’ every 15 minutes, you ‘examine’ every four hours, or every two if there is ‘lack of progress’. And if there still isn’t any progress, you offer to break the waters. To my credit, I started to make the connection fairly quickly into my journey that, if we saw meconium because we broke the waters artificially, we would then want to put on a continuous monitor which generally restricts movement. So we potentially break the waters 'to speed things up' and then we strap you to a monitor which 'slows things down' because you can no longer make good use of gravity or move intuitively anymore.

Flicking through my diary I see lots of reflections on the contradictions of modern maternity care but I had a blind spot: The premise that the modern obstetric and by extension the midwifery approach have made birth safer is not supported by statistics.

Is it not true that fewer mothers and babies die in childbirth today than ever?

Yes, it is! But the argument that it is because of our interventions is not supported by raw data.

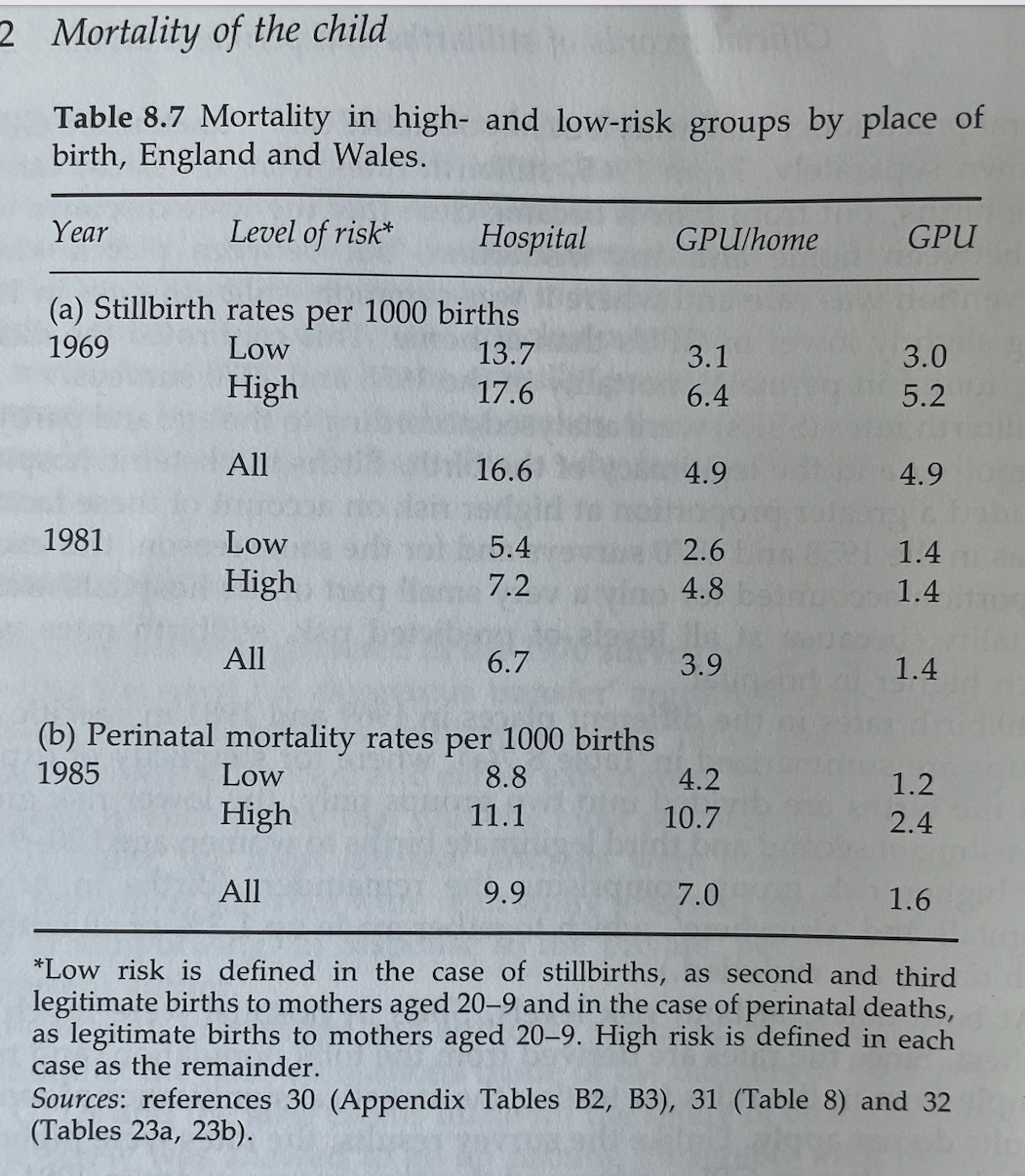

'Safer Childbirth? A critical history of maternity care' is a book written in 1990 by Marjorie Tew. Tew was teaching for the department of community health at Nottingham University in the 1970s about how to use available official statistics to study disease. She discovered 'to my complete surprise that the relevant routine statistics did not appear to support the widely held hypothesis that the increased hospitalisation of birth had caused the decline by then achieved in the mortality of mothers and their babies.' (p.viii - preface). The book is a compelling read authored by a woman who was neither a midwife nor a doctor. She claims total neutrality as an epidemiology researcher and teaching fellow and she revisits the history of midwifery and obstetrics starting at the time obstetricians first showed up on the stage. Without any supporting evidence, obstetricians proclaimed that their practices were superior and indeed safer than those of midwives, leaving midwives with the ambition to improve their training and regulate their profession. This is how midwifery gradually became absorbed by the medical model and physiological birth got replaced by industrial birth. Early epidemiological data shows clearly that hospital was less safe for babies in high and low risk groups. Tew offers official records of stillbirth and perinatal death in England and Wales by place of birth for the years of 1969, 1981 and 1985. This shows a general decline in overall stillbirth between '69 and '85. When comparing outcomes for home and GP units with hospital outcomes, however, babies were significantly more at risk in the hospital than out of hospital, so the overall decline in stillbirth cannot be attributed to the medicalisation of birth.

(Safer Childbirth? A critical history of maternity care, Marjorie Tew, p. 262)

So, the evidence had been there all along. We didn't really need the Birthplace UK study or the Lancet Study to prove that homebirth was not only safe, but safer than hospital birth for most women. Those are the studies that are often used by activists (including myself) to argue for the need for funding for homebirth teams and continuity of carer models. Occasionally funding does get allocated for innovative teams within the NHS but I have yet to see a sustained effort to support midwives in their desire to truly support women who want an undisturbed birth. Very often those teams lack long term support from management and from medically trained midwives due to the on call commitment it requires to provide a woman with a known midwife.

I still had to figure out most of this stuff and the days and weeks following baby O's birth had me believe that midwifery was making ground again. I was elated and motivated. It seemed possible to uphold physiological birth within the medical system whilst valuing and celebrating truly life saving medical interventions when they are needed.

There was a balance to be found somehow!

To be continued...